Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

The seeds of social revolution have been sown and sprouted. What we harvest is up to us.

If there is any potential catalyst for social upheaval that attracts less attention than extreme wealth inequality, it's mighty obscure. As I noted yesterday, the present extreme of wealth inequality draws an occasional bit of lip service or handwringing, but very little serious focus, despite ample historical foundations for its role in sowing the seeds of social revolutions.

As I tried to explain in yesterday's post, extreme wealth inequality might not be the spark that ignites a revolution, but it is a tectonic shift that destabilizes the social order. For extreme wealth inequality isn't a consequence of fate or sorcery; it is the consequence of policies that favor the few at the expense of the many, a reality that is exceedingly uncomfortable for those benefiting from the asymmetry.

For a rundown of the policies that have exacerbated wealth inequality, consider the following excerpts from Time magazine, September 2020: The Top 1% of Americans Have Taken $50 Trillion From the Bottom 90% -- And That's Made the U.S. Less Secure.

"There are some who blame the current plight of working Americans on structural changes in the underlying economy--on automation, and especially on globalization. According to this popular narrative, the lower wages of the past 40 years were the unfortunate but necessary price of keeping American businesses competitive in an increasingly cutthroat global market. But in fact, the $50 trillion transfer of wealth the RAND report documents has occurred entirely within the American economy, not between it and its trading partners. No, this upward redistribution of income, wealth, and power wasn't inevitable; it was a choice--a direct result of the trickle-down policies we chose to implement since 1975.

We chose to cut taxes on billionaires and to deregulate the financial industry. We chose to allow CEOs to manipulate share prices through stock buybacks, and to lavishly reward themselves with the proceeds. We chose to permit giant corporations, through mergers and acquisitions, to accumulate the vast monopoly power necessary to dictate both prices charged and wages paid. We chose to erode the minimum wage and the overtime threshold and the bargaining power of labor. For four decades, we chose to elect political leaders who put the material interests of the rich and powerful above those of the American people."

In other words, extreme wealth inequality is not the result of economic forces outside our control; it's the result of our policy responses to changing social, political and economic conditions. While those benefiting from the policies attribute the asymmetric distribution of the economy's gains to "forces outside our control" such as globalization and automation, those losing ground sense that this is an excuse for taking advantage of the situation, to the detriment of the national interest.

We can best understand extreme wealth inequality as the destabilizing result of one set of competing economic interests gaining dominance over other economic interests: broadly speaking, the balance between labor and capital has collapsed in favor of capital. To take one example, consider the minimum wage, which did not kept up with inflation for decades as a policy decision.

The different interests within each sector can also destabilize into asymmetric distributions. For example, within the broad category of capital, there are many competing interests: industrial capital, financial capital, land-based capital, domestic and global interests, and so on. Within labor, there are blue-collar and white collar interests, and gradations of skills, regional interests, and so on.

Broadly speaking, globalization and financialization greatly increased the share of some interests at the expense of others.

The social boundaries of what's acceptable and unacceptable change, enabling or restricting financial policies. For example, in the postwar boom of the 1950s, corporate CEOs earned multiples of their average employee that by today's standards were ludicrously low, as present-day CEOs routinely take home compensation (including stock options) that are in the tens of millions of dollars annually.

In the broad sweep of history, extreme asymmetries in the distribution of the economy's output are rebalanced one way or the other, if not with policy changes than by the overthrow of the status quo. The book The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century breaks down the various pieces of this complex puzzle.

The history and data are too varied to be easily summarized, but we can start with humanity's innate sense of fairness in social organizations: we sense when our contributions are getting short shrift while others are grabbing shares that are not commensurate with their contributions--despite their claims to "earning" their outsized shares.

Some write this off as envy, and to be sure envy is an innate human response, but fairness and envy are two different things. If someone strips us of power that we once held to benefit their own accumulation of wealth, our sense that this is unfair is not envy.

We seem to be approaching the point where a rebalancing of extreme asymmetries is at hand, and so we have to choose between policy changes and social upheaval. Those benefiting from the current asymmetrical distribution naturally feel that all is right with the world, while those whose purchasing power and political power have been stripmined feel that regaining what was taken from them is only fair.

Here's the data on our asymmetric distribution of wealth again. You can skip this if you've already seen the charts.

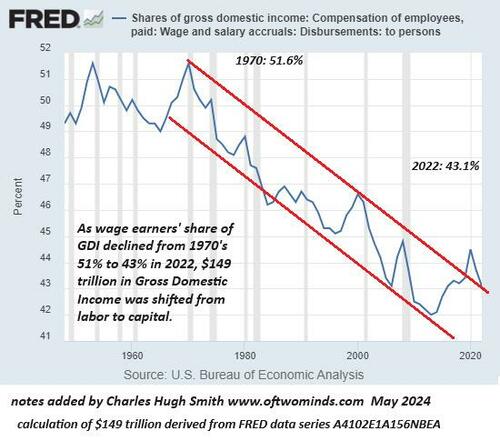

The RAND study Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018 concluded that capital siphoned $50 trillion from labor from 1975 to 2018.

Using data from the Federal Reserve's FRED database (series A4102E1A156NBEA), correspondent Alain M. calculated the actual sum for the period 1970 to 2022 (2022 being the most recent data available) was a staggering $149 trillion: his spreadsheet is available here as a PDF: Employees Share of Gross Domestic Income 1970-2022.

If wage earners' share of Gross Domestic Income had remained at 51% instead of declining to 43%, wage earners would have received an additional $149 trillion over those 52 years.

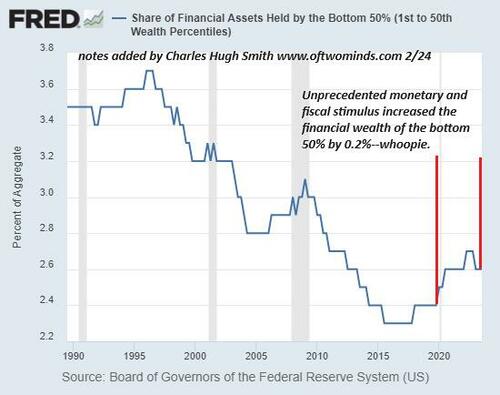

As GDP and household wealth have soared, he bottom 50% of American households' share of the nation's financial wealth has declined.

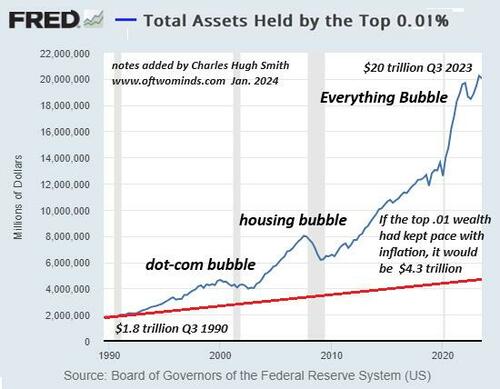

The top 0.01%'s wealth soared far above inflation.

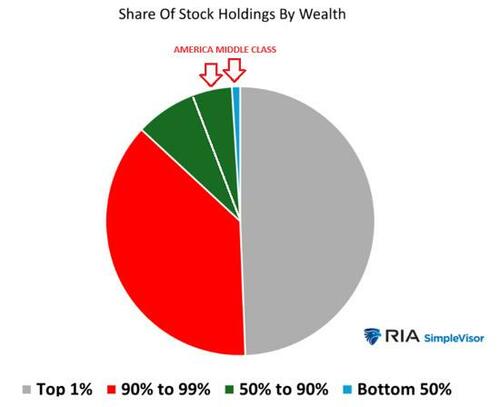

The ownership of stocks in concentrated in the top 10% households, who own 90% of this asset class.

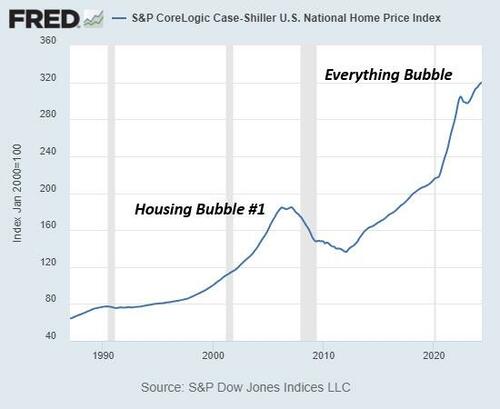

Housing prices have risen sharply, becoming unaffordable for the majority of households. Those who bought homes long ago in desirable areas have reaped enormous gains, a generational / class / regional asymmetry.

The seeds of social revolution have been sown and sprouted. What we harvest is up to us.

* * *

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

The seeds of social revolution have been sown and sprouted. What we harvest is up to us.

If there is any potential catalyst for social upheaval that attracts less attention than extreme wealth inequality, it's mighty obscure. As I noted yesterday, the present extreme of wealth inequality draws an occasional bit of lip service or handwringing, but very little serious focus, despite ample historical foundations for its role in sowing the seeds of social revolutions.

As I tried to explain in yesterday's post, extreme wealth inequality might not be the spark that ignites a revolution, but it is a tectonic shift that destabilizes the social order. For extreme wealth inequality isn't a consequence of fate or sorcery; it is the consequence of policies that favor the few at the expense of the many, a reality that is exceedingly uncomfortable for those benefiting from the asymmetry.

For a rundown of the policies that have exacerbated wealth inequality, consider the following excerpts from Time magazine, September 2020: The Top 1% of Americans Have Taken $50 Trillion From the Bottom 90% -- And That's Made the U.S. Less Secure.

"There are some who blame the current plight of working Americans on structural changes in the underlying economy--on automation, and especially on globalization. According to this popular narrative, the lower wages of the past 40 years were the unfortunate but necessary price of keeping American businesses competitive in an increasingly cutthroat global market. But in fact, the $50 trillion transfer of wealth the RAND report documents has occurred entirely within the American economy, not between it and its trading partners. No, this upward redistribution of income, wealth, and power wasn't inevitable; it was a choice--a direct result of the trickle-down policies we chose to implement since 1975.

We chose to cut taxes on billionaires and to deregulate the financial industry. We chose to allow CEOs to manipulate share prices through stock buybacks, and to lavishly reward themselves with the proceeds. We chose to permit giant corporations, through mergers and acquisitions, to accumulate the vast monopoly power necessary to dictate both prices charged and wages paid. We chose to erode the minimum wage and the overtime threshold and the bargaining power of labor. For four decades, we chose to elect political leaders who put the material interests of the rich and powerful above those of the American people."

In other words, extreme wealth inequality is not the result of economic forces outside our control; it's the result of our policy responses to changing social, political and economic conditions. While those benefiting from the policies attribute the asymmetric distribution of the economy's gains to "forces outside our control" such as globalization and automation, those losing ground sense that this is an excuse for taking advantage of the situation, to the detriment of the national interest.

We can best understand extreme wealth inequality as the destabilizing result of one set of competing economic interests gaining dominance over other economic interests: broadly speaking, the balance between labor and capital has collapsed in favor of capital. To take one example, consider the minimum wage, which did not kept up with inflation for decades as a policy decision.

The different interests within each sector can also destabilize into asymmetric distributions. For example, within the broad category of capital, there are many competing interests: industrial capital, financial capital, land-based capital, domestic and global interests, and so on. Within labor, there are blue-collar and white collar interests, and gradations of skills, regional interests, and so on.

Broadly speaking, globalization and financialization greatly increased the share of some interests at the expense of others.

The social boundaries of what's acceptable and unacceptable change, enabling or restricting financial policies. For example, in the postwar boom of the 1950s, corporate CEOs earned multiples of their average employee that by today's standards were ludicrously low, as present-day CEOs routinely take home compensation (including stock options) that are in the tens of millions of dollars annually.

In the broad sweep of history, extreme asymmetries in the distribution of the economy's output are rebalanced one way or the other, if not with policy changes than by the overthrow of the status quo. The book The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century breaks down the various pieces of this complex puzzle.

The history and data are too varied to be easily summarized, but we can start with humanity's innate sense of fairness in social organizations: we sense when our contributions are getting short shrift while others are grabbing shares that are not commensurate with their contributions--despite their claims to "earning" their outsized shares.

Some write this off as envy, and to be sure envy is an innate human response, but fairness and envy are two different things. If someone strips us of power that we once held to benefit their own accumulation of wealth, our sense that this is unfair is not envy.

We seem to be approaching the point where a rebalancing of extreme asymmetries is at hand, and so we have to choose between policy changes and social upheaval. Those benefiting from the current asymmetrical distribution naturally feel that all is right with the world, while those whose purchasing power and political power have been stripmined feel that regaining what was taken from them is only fair.

Here's the data on our asymmetric distribution of wealth again. You can skip this if you've already seen the charts.

The RAND study Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018 concluded that capital siphoned $50 trillion from labor from 1975 to 2018.

Using data from the Federal Reserve's FRED database (series A4102E1A156NBEA), correspondent Alain M. calculated the actual sum for the period 1970 to 2022 (2022 being the most recent data available) was a staggering $149 trillion: his spreadsheet is available here as a PDF: Employees Share of Gross Domestic Income 1970-2022.

If wage earners' share of Gross Domestic Income had remained at 51% instead of declining to 43%, wage earners would have received an additional $149 trillion over those 52 years.

As GDP and household wealth have soared, he bottom 50% of American households' share of the nation's financial wealth has declined.

The top 0.01%'s wealth soared far above inflation.

The ownership of stocks in concentrated in the top 10% households, who own 90% of this asset class.

Housing prices have risen sharply, becoming unaffordable for the majority of households. Those who bought homes long ago in desirable areas have reaped enormous gains, a generational / class / regional asymmetry.

The seeds of social revolution have been sown and sprouted. What we harvest is up to us.

* * *