By John Kemp, senior energy analyst at JKempEnergy

Europe’s gas inventories have depleted at the fastest rate for eight years, as the region has experienced repeated bouts of colder-than-normal temperatures and low wind speeds since the start of the winter heating season.

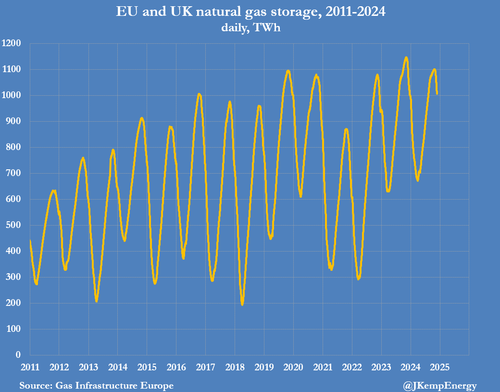

Combined inventories in underground storage across the European Union and the United Kingdom dropped by 83 terawatt-hours (TWh) between the official start of winter on October 1 and November 26.

Stocks have fallen more than four times faster than the average over the last ten years, and by the most for any year since 2016, according to data from operators compiled by Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE).

Inventories were still 58 TWh (+6% or +0.55 standard deviations) above the prior ten-year seasonal average on November 26, but the surplus had narrowed from 122 TWh (+13% or +1.38 standard deviations) at the start of winter.

Storage facilities across the region were 87% full on average, sharply lower than 97% on the same date in 2023 and 94% in 2022.

Northwest Europe has experienced a colder start to the winter this year, after exceptionally mild winters in 2023/24 and 2022/23, which has boosted heating demand.

With the heating season now approaching the 20% mark, Frankfurt has experienced 377 heating degree days, close to the average for the last ten years, but many more than in 2023 (303) and 2022 (345).

London has so far shivered through 327 heating degree days, the coldest start to the winter for five years, and well above the number in 2023 (268) and 2022 (219).

While colder temperatures have boosted heating demand, wind speeds in the North Sea have been below normal, cutting generation from offshore wind farms and forcing more reliance on gas-fired units.

Based on inventory movements over the last decade, EU and UK stocks are currently on course to end the winter around 468 TWh (with a likely range from 293 TWh to 573 TWh).

The projected carryout is already much lower than the 532 TWh (with a likely range from 349 TWh to 718 TWh) when the winter began.

On this course, inventories will end the winter almost 30% below record carryouts at the end of winter 2023/24 and 2022/23.

TOUGHER REFILL SEASON

Stocks are still comfortable but can no longer be described as plentiful and prices have risen to discourage consumption and attract more liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargoes to the region.

Front-month futures prices on the Dutch Title Transfer Facility have averaged €44 per megawatt-hour so far in November up from €36 in September and just €26 in February.

After adjusting for inflation, front-month prices in November are in the 87th percentile for all months since 2010 up from the 43rd percentile in February, signalling the need to conserve stocks and attract more supply.

But the greatest futures price increases have been for deliveries after this winter ends, in the second and third quarters of 2025.

Because of the much bigger depletion this winter, traders anticipate Europe will need to buy much more gas to refill its storage facilities in the summer of 2025 than was the case in the summers of 2024 and 2023.

Futures prices for the summer of 2025 (April-September) have recently traded as much as €4 per megawatt-hour above those for the winter of 2025/26 (October-March).

The unusual backwardation is a sign traders expect Europe will have to pay more next summer to refill storage and ensure stocks are back to a comfortable level ahead of winter 2025/26.

Europe will have to attract more LNG cargoes away from the fast-growing gas markets in Asia next summer and that implies higher prices.

In most seasonal commodity markets, the biggest risk of shortages comes not from a single disruption but repeated disruptions in successive years.

Inventories are normally enough to absorb one unexpected supply disruption or demand shock but that will leave them depleted and poorly prepared in the event of a second disruption or shock.

Europe’s major challenge is what would happen if winter 2024/25 remains colder-than-normal and is followed by another cold winter in 2025/26. To minimise that risk, depleted inventories will have to rebuilt during the summer of 2025, and traders are already betting that will prove expensive as Europe competes for more gas with fast-growing economies in Asia.

By John Kemp, senior energy analyst at JKempEnergy

Europe’s gas inventories have depleted at the fastest rate for eight years, as the region has experienced repeated bouts of colder-than-normal temperatures and low wind speeds since the start of the winter heating season.

Combined inventories in underground storage across the European Union and the United Kingdom dropped by 83 terawatt-hours (TWh) between the official start of winter on October 1 and November 26.

Stocks have fallen more than four times faster than the average over the last ten years, and by the most for any year since 2016, according to data from operators compiled by Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE).

Inventories were still 58 TWh (+6% or +0.55 standard deviations) above the prior ten-year seasonal average on November 26, but the surplus had narrowed from 122 TWh (+13% or +1.38 standard deviations) at the start of winter.

Storage facilities across the region were 87% full on average, sharply lower than 97% on the same date in 2023 and 94% in 2022.

Northwest Europe has experienced a colder start to the winter this year, after exceptionally mild winters in 2023/24 and 2022/23, which has boosted heating demand.

With the heating season now approaching the 20% mark, Frankfurt has experienced 377 heating degree days, close to the average for the last ten years, but many more than in 2023 (303) and 2022 (345).

London has so far shivered through 327 heating degree days, the coldest start to the winter for five years, and well above the number in 2023 (268) and 2022 (219).

While colder temperatures have boosted heating demand, wind speeds in the North Sea have been below normal, cutting generation from offshore wind farms and forcing more reliance on gas-fired units.

Based on inventory movements over the last decade, EU and UK stocks are currently on course to end the winter around 468 TWh (with a likely range from 293 TWh to 573 TWh).

The projected carryout is already much lower than the 532 TWh (with a likely range from 349 TWh to 718 TWh) when the winter began.

On this course, inventories will end the winter almost 30% below record carryouts at the end of winter 2023/24 and 2022/23.

TOUGHER REFILL SEASON

Stocks are still comfortable but can no longer be described as plentiful and prices have risen to discourage consumption and attract more liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargoes to the region.

Front-month futures prices on the Dutch Title Transfer Facility have averaged €44 per megawatt-hour so far in November up from €36 in September and just €26 in February.

After adjusting for inflation, front-month prices in November are in the 87th percentile for all months since 2010 up from the 43rd percentile in February, signalling the need to conserve stocks and attract more supply.

But the greatest futures price increases have been for deliveries after this winter ends, in the second and third quarters of 2025.

Because of the much bigger depletion this winter, traders anticipate Europe will need to buy much more gas to refill its storage facilities in the summer of 2025 than was the case in the summers of 2024 and 2023.

Futures prices for the summer of 2025 (April-September) have recently traded as much as €4 per megawatt-hour above those for the winter of 2025/26 (October-March).

The unusual backwardation is a sign traders expect Europe will have to pay more next summer to refill storage and ensure stocks are back to a comfortable level ahead of winter 2025/26.

Europe will have to attract more LNG cargoes away from the fast-growing gas markets in Asia next summer and that implies higher prices.

In most seasonal commodity markets, the biggest risk of shortages comes not from a single disruption but repeated disruptions in successive years.

Inventories are normally enough to absorb one unexpected supply disruption or demand shock but that will leave them depleted and poorly prepared in the event of a second disruption or shock.

Europe’s major challenge is what would happen if winter 2024/25 remains colder-than-normal and is followed by another cold winter in 2025/26. To minimise that risk, depleted inventories will have to rebuilt during the summer of 2025, and traders are already betting that will prove expensive as Europe competes for more gas with fast-growing economies in Asia.