By Elwin de Groot, head of macro strategy at Rabobank

“We can’t rely on tax revenues to keep flowing – we need economic growth”, was German Finance Minister Lindner’s response to the latest estimate of the expected tax take for the German federal government for the five years up till 2028. This tax estimate – compiled twice a year by a broad working group – now looks to be some EUR12.6bn smaller than when it was estimated back in May. Speaking at the sidelines of the IMF meeting in Washington, Lindner’s second point was that, the country will “have to consolidate further”.

Now, if you have less money to spend, you have to, well, spend less money. Right? And of course, one would like to avoid a situation where investors would start to doubt the sustainability of the country’s government finances. But with a public debt ratio of just 63%, Germany, arguably, is a long way from that. And Germany is neither a company nor a household. That former Chancellor and ‘powerwoman’, Angela Merkel regularly invoked the thrifty schwäbische Hausfrau only strengthens the point: German frugality may well have been the reason why it is now where it is. So, unless there is reason to think that some of the current money isn’t being spent well or efficiently, curbing spending is likely to have consequences for growth. Indeed, the cure could well prove worse than the disease, seen against a backdrop of the strategic challenges (read: need to invest) Germany is facing.

So an important question is what Lindner thinks is necessary to revive growth in the economy. If his answer is “more dynamism” (words he used yesterday) by revving up the German export engine, he may find that this business model risks crushing into a wall of protectionism anytime soon. There is at least one US presidential candidate out there who believes there are too many German cars in the US. And stable demand from China nowadays is far from certain.

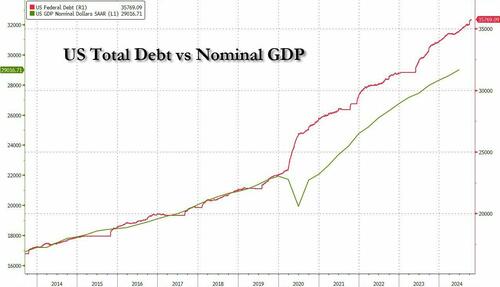

[And speaking of American growth and deficit, just one chart]

This is probably why Chancellor Scholz, escorted by a business delegation, arrived in Delhi yesterday for a three-day visit of the country and PM Modi. The Chancellor is looking to strengthen business ties, open up new markets for its exporters but also to discuss India’s potential to supply skilled labor for German companies who are facing a rapidly ageing and declining work force over the next decades. This suggests Germany is looking to diversify its export markets but is also keen to keep with its export-oriented model. Key example here is its aim to sell India six (co-produced) submarines (instead of building them for its own fleet).

But if the doctor’s diagnosis is that the German economy needs a ‘strategic injection’ of reforms, setting new priorities, raising innovation and reducing its raw material dependencies, without losing the support of its population and workforce – to name a few things, then it is questionable whether that can be achieved with belt-tightening. For what often happens is that all spending ministries are expected to share the burden, as prioritizing is politically much more difficult to achieve. (This certainly seems to hold right now with the German coalition looking fragile, although POLITICO argues that a Trump victory may actually force parties to cling together).

And if Lindner thinks that the answer should be to strengthen German (or European) domestic demand, one could also question whether belt-tightening is the right response at this juncture. Unless the German leadership suddenly believes that this task falls upon the ECB! In any case, it surely is not what the pundits are currently advising the Chinese government to do in order to stabilize its real estate sector and to stimulate the economy. Case in point is the cold reception of China’s recent stimulus plans by central bankers and other policy makers at the IMF gathering this week, with Treasury Secretary Yellen saying the measures so far announced fail to tackle overcapacity and weak Chinese domestic demand. China’s reluctance to announce big fiscal stimulus right now may also depend on the US election outcome.

Both of these factors have also been weighing on markets and perhaps also on business sentiment lately. Which brings us to the PMI’s. Although the German PMI surveys came in somewhat higher than expected for October, this was overshadowed by a weaker survey for France. As a result, the Eurozone manufacturing PMI manufacturing turned out a little better (45.9 compared to 45.1 consensus), whilst the services PMI came in a tad weaker at 51.2 (compared to 51.5 consensus). The gap with the US survey widened again, with the US services PMI up a notch (+0.1) and manufacturing up 0.5 points (but also remaining below the neutral 50-mark).

As we have noted before, a repeat pattern has slipped into the Eurozone services PMI since 2021 and this means that index tends to fall from April/May until the last months of the year, after which it rebounds. This doesn't mean that yesterday’s surveys were ‘good’, but the hard data so far (which, for most sectors, is still only available up to July) appear to be holding up better. That said, manufacturing remains in the doldrums whilst growth in services may only just offset this.

The UK’s output PMI fell to an 11-month low at 51.7, driven by declines in both manufacturing (50.3) and services (51.8). While this still indicates expansion, it's at a much more moderate pace than in previous months. Historically, this aligns with a growth rate of about 0.1-0.2% per quarter. Survey respondents attribute this to pre-Budget uncertainty and gloomy government rhetoric. The upcoming US election is also an important factor.

As our UK strategist argues:

“the broad contours of what Chancellor Reeves will announce on October 30 are now clear: she plans to raise taxes on capital to fund higher day-to-day spending, while altering fiscal rules to allow for more borrowing for capital projects. It could 'free up' some GBP 50bn compared to unchanged fiscal rules. The speed at which this money is deployed will be crucial (e.g. in the Netherlands we have learnt that this is easier said than done) but we believe the overall effect of Reeves' budget will be slightly looser, not tighter. This should support future growth and does not signal a return to austerity.”

We anticipate the Bank of England will argue that the Budget has little net effect on the balance between demand and supply, as they don't want to be seen to 'thwart' increased public investment and if a gov't wants to add debt they could of course also use some lower (real) interest rates. The Bank is already on a path of gradual easing, and based on Bailey’s comments yesterday, it seems likely to continue.

By Elwin de Groot, head of macro strategy at Rabobank

“We can’t rely on tax revenues to keep flowing – we need economic growth”, was German Finance Minister Lindner’s response to the latest estimate of the expected tax take for the German federal government for the five years up till 2028. This tax estimate – compiled twice a year by a broad working group – now looks to be some EUR12.6bn smaller than when it was estimated back in May. Speaking at the sidelines of the IMF meeting in Washington, Lindner’s second point was that, the country will “have to consolidate further”.

Now, if you have less money to spend, you have to, well, spend less money. Right? And of course, one would like to avoid a situation where investors would start to doubt the sustainability of the country’s government finances. But with a public debt ratio of just 63%, Germany, arguably, is a long way from that. And Germany is neither a company nor a household. That former Chancellor and ‘powerwoman’, Angela Merkel regularly invoked the thrifty schwäbische Hausfrau only strengthens the point: German frugality may well have been the reason why it is now where it is. So, unless there is reason to think that some of the current money isn’t being spent well or efficiently, curbing spending is likely to have consequences for growth. Indeed, the cure could well prove worse than the disease, seen against a backdrop of the strategic challenges (read: need to invest) Germany is facing.

So an important question is what Lindner thinks is necessary to revive growth in the economy. If his answer is “more dynamism” (words he used yesterday) by revving up the German export engine, he may find that this business model risks crushing into a wall of protectionism anytime soon. There is at least one US presidential candidate out there who believes there are too many German cars in the US. And stable demand from China nowadays is far from certain.

[And speaking of American growth and deficit, just one chart]

This is probably why Chancellor Scholz, escorted by a business delegation, arrived in Delhi yesterday for a three-day visit of the country and PM Modi. The Chancellor is looking to strengthen business ties, open up new markets for its exporters but also to discuss India’s potential to supply skilled labor for German companies who are facing a rapidly ageing and declining work force over the next decades. This suggests Germany is looking to diversify its export markets but is also keen to keep with its export-oriented model. Key example here is its aim to sell India six (co-produced) submarines (instead of building them for its own fleet).

But if the doctor’s diagnosis is that the German economy needs a ‘strategic injection’ of reforms, setting new priorities, raising innovation and reducing its raw material dependencies, without losing the support of its population and workforce – to name a few things, then it is questionable whether that can be achieved with belt-tightening. For what often happens is that all spending ministries are expected to share the burden, as prioritizing is politically much more difficult to achieve. (This certainly seems to hold right now with the German coalition looking fragile, although POLITICO argues that a Trump victory may actually force parties to cling together).

And if Lindner thinks that the answer should be to strengthen German (or European) domestic demand, one could also question whether belt-tightening is the right response at this juncture. Unless the German leadership suddenly believes that this task falls upon the ECB! In any case, it surely is not what the pundits are currently advising the Chinese government to do in order to stabilize its real estate sector and to stimulate the economy. Case in point is the cold reception of China’s recent stimulus plans by central bankers and other policy makers at the IMF gathering this week, with Treasury Secretary Yellen saying the measures so far announced fail to tackle overcapacity and weak Chinese domestic demand. China’s reluctance to announce big fiscal stimulus right now may also depend on the US election outcome.

Both of these factors have also been weighing on markets and perhaps also on business sentiment lately. Which brings us to the PMI’s. Although the German PMI surveys came in somewhat higher than expected for October, this was overshadowed by a weaker survey for France. As a result, the Eurozone manufacturing PMI manufacturing turned out a little better (45.9 compared to 45.1 consensus), whilst the services PMI came in a tad weaker at 51.2 (compared to 51.5 consensus). The gap with the US survey widened again, with the US services PMI up a notch (+0.1) and manufacturing up 0.5 points (but also remaining below the neutral 50-mark).

As we have noted before, a repeat pattern has slipped into the Eurozone services PMI since 2021 and this means that index tends to fall from April/May until the last months of the year, after which it rebounds. This doesn't mean that yesterday’s surveys were ‘good’, but the hard data so far (which, for most sectors, is still only available up to July) appear to be holding up better. That said, manufacturing remains in the doldrums whilst growth in services may only just offset this.

The UK’s output PMI fell to an 11-month low at 51.7, driven by declines in both manufacturing (50.3) and services (51.8). While this still indicates expansion, it's at a much more moderate pace than in previous months. Historically, this aligns with a growth rate of about 0.1-0.2% per quarter. Survey respondents attribute this to pre-Budget uncertainty and gloomy government rhetoric. The upcoming US election is also an important factor.

As our UK strategist argues:

“the broad contours of what Chancellor Reeves will announce on October 30 are now clear: she plans to raise taxes on capital to fund higher day-to-day spending, while altering fiscal rules to allow for more borrowing for capital projects. It could 'free up' some GBP 50bn compared to unchanged fiscal rules. The speed at which this money is deployed will be crucial (e.g. in the Netherlands we have learnt that this is easier said than done) but we believe the overall effect of Reeves' budget will be slightly looser, not tighter. This should support future growth and does not signal a return to austerity.”

We anticipate the Bank of England will argue that the Budget has little net effect on the balance between demand and supply, as they don't want to be seen to 'thwart' increased public investment and if a gov't wants to add debt they could of course also use some lower (real) interest rates. The Bank is already on a path of gradual easing, and based on Bailey’s comments yesterday, it seems likely to continue.