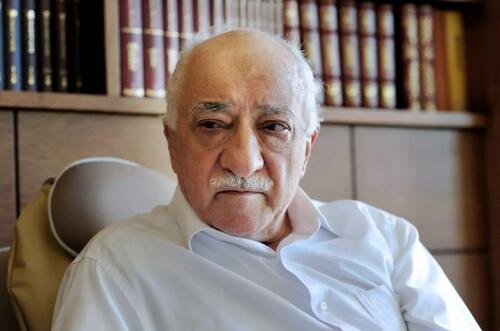

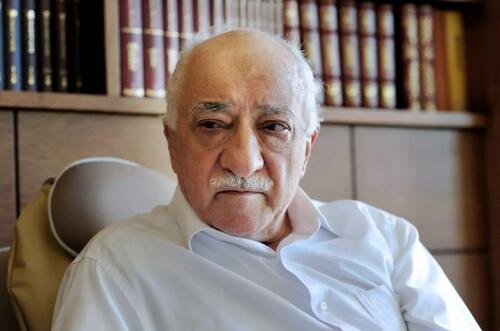

Fethullah Gulen, the Turkish religious leader who founded the Gulen Movement, has died in the US state of Pennsylvania on Sunday night aged 83. Gulen and his movement were accused by the Turkish government of masterminding a failed military coup in July 2016, which left hundreds of Turks dead.

The movement itself denied involvement in the attempt to depose the Turkish government but its role in the coup attempt is accepted across Turkish society and even amongst opponents of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Herkul, an official website that releases announcements on Gulen’s activities, reported that the religious leader passed away at a hospital where he was undergoing treatment for chronic illnesses. A detailed report on his health condition and information about his funeral would be released later, it added.

Gulen’s death symbolizes the end of an era in Turkish politics. Born in 1941, Gulen established himself as an imam in Turkey in the 1970s and eventually set up a well-organized religious movement to disseminate his beliefs. The movement spread globally through a network of Turkish schools in more than 100 countries.

Functioning as an organization built around the figure of Gulen, the movement claimed to follow the teachings of late Islamic cleric and Sufi, Said Nursi.

Gulen transformed the group into a fully fledged political movement, whose followers practiced a form of entryism, in which they actively recruited individuals and placed them into key state institutes such as the police, judiciary and military.

Initial alliance

Early on in this endeavor, the Gulen movement's policies dovetailed with the mainstream religious conservative movement, led by current Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Conservatives welcomed attempts to make the military and judiciary less hostile to religious groups, as those institutions were pivotal in suppressing the role of Islam in politics throughout Turkey's modern history.

Within this climate of repression, Gulen moved to the US 1999, citing health reasons, and never returned to Turkey. From his base in the US, Gulen's movement established schools, a media conglomerate with magazines, newspapers, and TV stations, as well business unions.

Networks of dormitories and student houses operating under the Gulen banner were used as a recruiting ground for the movement. Well-educated or bright potential members were chosen and had their identities masked or downplayed in order to easily enter government service.

When Erdogan entered office as prime minister in 2003, Gulen already had a large network of followers within the state, which was previously dominated by Turkish nationalists, secularists and others.

Erdogan allied himself with Gulen over the years to strengthen his own influence over the police and judiciary, as well as to undercut the military’s influence over politics. The alliance succeeded in bringing about constitutional changes in 2010 and Gulen-linked individuals dominated top judicial positions.

What followed were indictments against top generals and other powerful figures in the state who were accused of plotting to overthrow Erdogan, further dampening the role of the military in Turkish politics.

Break with Erdogan

Erdogan’s first crack with Gulen occurred during the Israeli attack on a Gaza flotilla in 2010 when nine Turkish citizens were killed by Israeli soldiers on board the Mavi Marmara, a ship attempting to break the siege on the people of Gaza.

Gulen criticized the flotilla as being too risky and slammed the government for permitting the boat to sail. Another sore point was the 2013 peace process between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which Gulen opposed.

Tensions simmered through the 2013 Gezi Park protests, as Gulen decided on a position of neutrality as anti-government protesters staged the most serious civil unrest against AKP rule since it took power in 2002.

The final break was a December 2013 corruption inquiry into three ministers within the Erodgan government. Erdogan accused Gulen and his movement of trying to use his people in the judiciary and police to topple his government through trumped-up charges.

After Erdogan won local elections a few months after the inquiry, he began his move against the Gulen movement, removing individuals associated with the group from state service, as well as declaring them terrorists.

The government also went after Gulen-linked companies, media outlets, and schools. This crackdown intensified after the 2016 coup attempt, after which widescale purges resulted in the dismissal and arrest of tens of thousands of civil servants and other state employees through emergency powers.

The Turkish state officially references the Gulen organization as a terror group...

FETO terror group ringleader Fetullah Gulen dies in US pic.twitter.com/NwTW4oTx2n

— TRT World Now (@TRTWorldNow) October 21, 2024

Gulen’s presence in the US also became a point of tension with Washington, which did not immediately condemn the coup attempt. Ankara's official demand for the US to return the cleric to Turkey were repeatedly ignored by the Americans, with Washington insisting there was not enough evidence implicating Gulen in the plot.

For its part, the Gulen Movement, which operates more than 100 charter schools in the US, has established lobbying groups to pressure Congress on alleged human rights abuses taking place in Turkey.

The group is, however, itself marred with division. Gulen's nephew, Ebuseleme Gulen, earlier this year accused the movement's leadership of knowing and approving the 2016 coup attempt by empowering people close to Gulen to participate in the insurrection while misleading Gulen about their involvement.

Turkish sources familiar with the issue told media on Monday that there would be a leadership crisis within the movement following Gulen's death. The sources said Cevdet Turkyolu, one of Gulen's lieutenants in Pennslyvania, and Abdullah Aymaz, the current leader of the group in Europe, are expected to compete for the top position in the coming days.

Fethullah Gulen, the Turkish religious leader who founded the Gulen Movement, has died in the US state of Pennsylvania on Sunday night aged 83. Gulen and his movement were accused by the Turkish government of masterminding a failed military coup in July 2016, which left hundreds of Turks dead.

The movement itself denied involvement in the attempt to depose the Turkish government but its role in the coup attempt is accepted across Turkish society and even amongst opponents of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Herkul, an official website that releases announcements on Gulen’s activities, reported that the religious leader passed away at a hospital where he was undergoing treatment for chronic illnesses. A detailed report on his health condition and information about his funeral would be released later, it added.

Gulen’s death symbolizes the end of an era in Turkish politics. Born in 1941, Gulen established himself as an imam in Turkey in the 1970s and eventually set up a well-organized religious movement to disseminate his beliefs. The movement spread globally through a network of Turkish schools in more than 100 countries.

Functioning as an organization built around the figure of Gulen, the movement claimed to follow the teachings of late Islamic cleric and Sufi, Said Nursi.

Gulen transformed the group into a fully fledged political movement, whose followers practiced a form of entryism, in which they actively recruited individuals and placed them into key state institutes such as the police, judiciary and military.

Initial alliance

Early on in this endeavor, the Gulen movement's policies dovetailed with the mainstream religious conservative movement, led by current Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Conservatives welcomed attempts to make the military and judiciary less hostile to religious groups, as those institutions were pivotal in suppressing the role of Islam in politics throughout Turkey's modern history.

Within this climate of repression, Gulen moved to the US 1999, citing health reasons, and never returned to Turkey. From his base in the US, Gulen's movement established schools, a media conglomerate with magazines, newspapers, and TV stations, as well business unions.

Networks of dormitories and student houses operating under the Gulen banner were used as a recruiting ground for the movement. Well-educated or bright potential members were chosen and had their identities masked or downplayed in order to easily enter government service.

When Erdogan entered office as prime minister in 2003, Gulen already had a large network of followers within the state, which was previously dominated by Turkish nationalists, secularists and others.

Erdogan allied himself with Gulen over the years to strengthen his own influence over the police and judiciary, as well as to undercut the military’s influence over politics. The alliance succeeded in bringing about constitutional changes in 2010 and Gulen-linked individuals dominated top judicial positions.

What followed were indictments against top generals and other powerful figures in the state who were accused of plotting to overthrow Erdogan, further dampening the role of the military in Turkish politics.

Break with Erdogan

Erdogan’s first crack with Gulen occurred during the Israeli attack on a Gaza flotilla in 2010 when nine Turkish citizens were killed by Israeli soldiers on board the Mavi Marmara, a ship attempting to break the siege on the people of Gaza.

Gulen criticized the flotilla as being too risky and slammed the government for permitting the boat to sail. Another sore point was the 2013 peace process between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which Gulen opposed.

Tensions simmered through the 2013 Gezi Park protests, as Gulen decided on a position of neutrality as anti-government protesters staged the most serious civil unrest against AKP rule since it took power in 2002.

The final break was a December 2013 corruption inquiry into three ministers within the Erodgan government. Erdogan accused Gulen and his movement of trying to use his people in the judiciary and police to topple his government through trumped-up charges.

After Erdogan won local elections a few months after the inquiry, he began his move against the Gulen movement, removing individuals associated with the group from state service, as well as declaring them terrorists.

The government also went after Gulen-linked companies, media outlets, and schools. This crackdown intensified after the 2016 coup attempt, after which widescale purges resulted in the dismissal and arrest of tens of thousands of civil servants and other state employees through emergency powers.

The Turkish state officially references the Gulen organization as a terror group...

FETO terror group ringleader Fetullah Gulen dies in US pic.twitter.com/NwTW4oTx2n

— TRT World Now (@TRTWorldNow) October 21, 2024

Gulen’s presence in the US also became a point of tension with Washington, which did not immediately condemn the coup attempt. Ankara's official demand for the US to return the cleric to Turkey were repeatedly ignored by the Americans, with Washington insisting there was not enough evidence implicating Gulen in the plot.

For its part, the Gulen Movement, which operates more than 100 charter schools in the US, has established lobbying groups to pressure Congress on alleged human rights abuses taking place in Turkey.

The group is, however, itself marred with division. Gulen's nephew, Ebuseleme Gulen, earlier this year accused the movement's leadership of knowing and approving the 2016 coup attempt by empowering people close to Gulen to participate in the insurrection while misleading Gulen about their involvement.

Turkish sources familiar with the issue told media on Monday that there would be a leadership crisis within the movement following Gulen's death. The sources said Cevdet Turkyolu, one of Gulen's lieutenants in Pennslyvania, and Abdullah Aymaz, the current leader of the group in Europe, are expected to compete for the top position in the coming days.