Authored by Ryan McMaken via The Mises Institute,

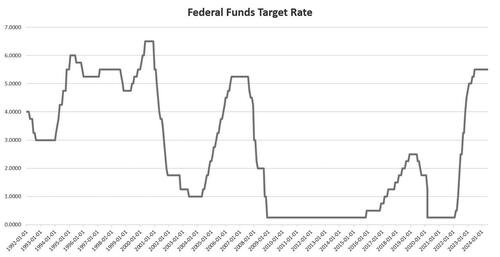

The Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) last week left the target policy interest rate (the federal funds rate) unchanged at 5.5 percent. The target rate has now been flat at 5.5 percent since July of 2023—as the Fed waits and hopes that everything will turn out fine. In his prepared remarks at Wednesday’s FOMC press conference, Powell continued with the soothing message he has generally employed at these press conferences over the past year. The general message has been one of moderate but sustained growth, and an economy marked by “strong” employment trends and moderating inflation.

Powell then combined this view of the economy with a general narrative on Fed policy in which the FOMC will hold steady until the committee believes that inflation is returning to the “long-run target of two-percent inflation.” Once the Fed is “confident” that the target inflation level has been secured, then the Fed will begin cutting the target interest rate, and this will then send the economy back into another expansion phase.

Through it all, Powell and the FOMC insist that there will be no significant bumps in the road and a “soft landing” will be achieved. That is, Powell and the Fed repeatedly tell the public that the Fed will thread the needle of pulling down price inflation while also ensuring that the economy continues to grow at solid rates while employment remains strong.

But there are two problems with this narrative: The first is that the Fed has never actually managed to pull this off—at least not at any time in the last 45 years. In actual experience, this is what happens: the Fed denies there is a recession approaching well until after the recession has begun. Then, the Fed cuts interest rates after unemployment has already begun to march upward.

The second problem with the narrative is that the Fed is not motivated simply by concerns over the state of employment and the economy. Yes, the Fed would have us believe that it cares only about an unbiased reading of economic data, and that Fed policy is guided by this alone. When the Fed claims to be “data driven” this is what it means. In reality, the Fed is deeply concerned with something else entirely: keeping interest rates low so that the federal government can continue to borrow enormous amounts of money at low yields. The more the federal government adds to its enormous debt, the more pressure there will be on the central bank to keep rates low and send them lower.

Yes, it’s true the Fed fears price inflation because price inflation causes political instability. When this fear wins out, the fed lets interest rates rise. But, the Federal Treasury also expects the Fed to keep interest rates low for the elites in the federal government who never tire of deficit spending. When the “need” for deficit spending wins out, the Fed forces interest rates down. These two goals are directly opposed to each other. Unfortunately, if the Fed has to choose between the two, it is likely to choose the path of lower interest rates and rising price inflation.

How “Soft Landings” Really Happen

Let’s first look at the “soft landing” myth. Talk about “soft landings” have been common in the mas media since at least the recession of 2001. As late as July of 2001, for example, Bloomberg authors were speculating about how soft the soft landing would be. It eventually turned out there was no soft landing and the Dot-Com bust soon followed.

“Soft landing” talk was even more prominent in the lead-up to the Great Recession. As late as mid-2008, months after the recession had already begun, fed Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke was predicting a soft landing and that there would be no recession at all. In that recession, the unemployment rate reached 9.9 percent.

We see this all at work again right now. A look at the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) shows that Fed officials are committed to claiming there will be no recession and economic growth will continue on a slow, steady, and positive trajectory. Yes, the SEP suggests the Fed will soon begin to lower interest rates, but in this fantasy version of the economy, that will be followed by continued economic growth and stable employment.

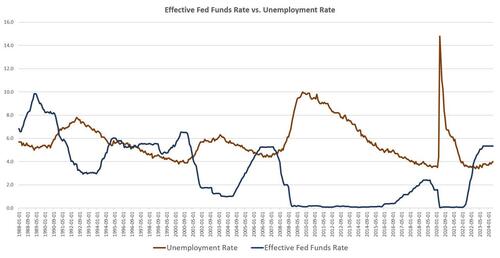

That’s not what happens in real life, though. Note, for example, that over the past 30-plus years, that Fed rate cuts did not cap off a “soft landing,” but actually preceded the most vigorous period of job losses. As can be seen in the graph, cuts to the federal funds rate come several months before sizable increases in the unemployment rate. Sharp rate cuts began in 1990, for example, and the 1991 recession soon followed. Similarly, the Fed began to cut rates in late 2000, and then the unemployment rate soon accelerated upward. This again happened in 2007 when unemployment began to mount shortly after Fed rate cuts.

I’m not saying that the cuts to the federal funds rate caused rising unemployment, of course. I’m saying that the Fed knew there was no soft landing in the works, and knew that recessions were on the way. That’s why the Fed hit the panic button when it did, and cut rates in hopes of shortening the coming recession.

This reality makes it clear that there is absolutely no reason to believe Fed claims that it has everything under control, and that rate cuts will come only after the Fed has tightened just enough to rein in inflation without popping the many bubbles that fueled employment and consumer spending in the lead up to the recession.

In summary, this is how it has really worked: fearful that inflation is getting out of control, the Fed will raise the target interest rate and generally “tighten” monetary policy. Through it all, the Fed will insist there is no recession on the horizon and that a “soft landing” is in the works. Eventually, however, it becomes clear that the economy is substantially weakening and the Fed has been either lying about the economy or has been simply wrong. At that point the Fed then then does what it always does (in recent decades) when it fears a recession: it loosens monetary policy in hopes of blowing up a whole new series of bubbles to create a new boom period.

This is far cry from the sedate, measured, and perfectly controlled story of monetary policy that the Fed would have us believe.

The Fed Exists to Keep the Federal Government Funded with Easy Money

The second problem with Powell’s narrative is that the Fed is not motivated simply be concerns over the state of employment and the economy. While it would be nice to think the Fed is primarily concerned with the “everyman” and his job prospects, the reality is that the Fed is very much concerned with keeping borrowing costs low so that Mitch McConnell, Nancy Pelosi, et al, can keep buying votes and fueling the warfare-welfare state with enormous amounts of deficit spending.

Keeping borrowing costs low—by forcing down interest rates—is now more important than it has been in many decades. Over the past four years, the total federal debt has skyrocketed by 11 trillion dollars from $23 trillion to $34 trillion. In an environment of near-zero interest rates, this might be manageable. However, when this kind of debt is combined with rising interest rates, interest payments are rapidly rising and consuming ever larger portions of the federal budget. If the regime is not careful it could face a sovereign debt crisis.

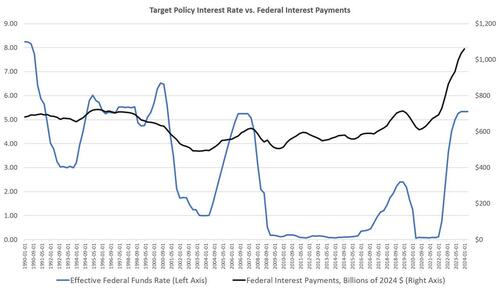

When the Fed is able to force interest rates down without fear of runaway inflation, rising debt is not much of an urgent problem. As we can see in the graph, a rapidly rising federal debt did not lead to sizable growth in interest costs in the wake of the Great Depression. That, however, was during a period of very low interest rates. Since 2022, however, Interest costs on the debt have rocketed upward as the Fed has been forced to allow interest rates to rise.

In fact, interest costs have more than doubled since 2021. Yet, we’re not even seeing the full impact of mounting debt combined with rising interest rates. Interest costs over the past few years have been kept somewhat under control by the fact that federal debt does not mature all at once. In 2024, however, nearly 9 trillion dollars worth of federal debt will mature. That will need to be replaced with new debt which will need to be paid off at higher interest rates (i.e., at higher yields) than the maturing debt. Combined with the $2 trillion or so in new debt that will be added in 2024, the Federal government will need somebody to buy more than 10 trillion dollars worth of federal debt. That a whole lot of debt and the Fed will be expected to help the federal government somehow keep interest rates from rising further. This will require the Fed to enter the marketplace and buy up large amounts of debt in order to push down yields.

In other words, political realities will mean the Fed will have to embrace new rate cuts whether price inflation is at the two-percent goal or not. The Fed will say that price inflation has hit the “target” regardless of whether or not that is the reality. Since the Fed now defines its two-percent target in terms of averages and long-term trends, the Fed need only say that it has determined that the “trend” points toward falling price inflation.

Then, voilà, the Fed can get to doing what really matters to the federal government: laundering federal deficits by forcing down interest rates.

Yesterday, Jay Powell performed the usual song-and-dance that is the foundation of the central bank’s political legitimacy: claim it is skillfully managing the economy while claiming to be deeply concerned about the daily struggles of ordinary people who face the ravages of price inflation. The reality behind this routine is something very different.

Authored by Ryan McMaken via The Mises Institute,

The Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) last week left the target policy interest rate (the federal funds rate) unchanged at 5.5 percent. The target rate has now been flat at 5.5 percent since July of 2023—as the Fed waits and hopes that everything will turn out fine. In his prepared remarks at Wednesday’s FOMC press conference, Powell continued with the soothing message he has generally employed at these press conferences over the past year. The general message has been one of moderate but sustained growth, and an economy marked by “strong” employment trends and moderating inflation.

Powell then combined this view of the economy with a general narrative on Fed policy in which the FOMC will hold steady until the committee believes that inflation is returning to the “long-run target of two-percent inflation.” Once the Fed is “confident” that the target inflation level has been secured, then the Fed will begin cutting the target interest rate, and this will then send the economy back into another expansion phase.

Through it all, Powell and the FOMC insist that there will be no significant bumps in the road and a “soft landing” will be achieved. That is, Powell and the Fed repeatedly tell the public that the Fed will thread the needle of pulling down price inflation while also ensuring that the economy continues to grow at solid rates while employment remains strong.

But there are two problems with this narrative: The first is that the Fed has never actually managed to pull this off—at least not at any time in the last 45 years. In actual experience, this is what happens: the Fed denies there is a recession approaching well until after the recession has begun. Then, the Fed cuts interest rates after unemployment has already begun to march upward.

The second problem with the narrative is that the Fed is not motivated simply by concerns over the state of employment and the economy. Yes, the Fed would have us believe that it cares only about an unbiased reading of economic data, and that Fed policy is guided by this alone. When the Fed claims to be “data driven” this is what it means. In reality, the Fed is deeply concerned with something else entirely: keeping interest rates low so that the federal government can continue to borrow enormous amounts of money at low yields. The more the federal government adds to its enormous debt, the more pressure there will be on the central bank to keep rates low and send them lower.

Yes, it’s true the Fed fears price inflation because price inflation causes political instability. When this fear wins out, the fed lets interest rates rise. But, the Federal Treasury also expects the Fed to keep interest rates low for the elites in the federal government who never tire of deficit spending. When the “need” for deficit spending wins out, the Fed forces interest rates down. These two goals are directly opposed to each other. Unfortunately, if the Fed has to choose between the two, it is likely to choose the path of lower interest rates and rising price inflation.

How “Soft Landings” Really Happen

Let’s first look at the “soft landing” myth. Talk about “soft landings” have been common in the mas media since at least the recession of 2001. As late as July of 2001, for example, Bloomberg authors were speculating about how soft the soft landing would be. It eventually turned out there was no soft landing and the Dot-Com bust soon followed.

“Soft landing” talk was even more prominent in the lead-up to the Great Recession. As late as mid-2008, months after the recession had already begun, fed Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke was predicting a soft landing and that there would be no recession at all. In that recession, the unemployment rate reached 9.9 percent.

We see this all at work again right now. A look at the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) shows that Fed officials are committed to claiming there will be no recession and economic growth will continue on a slow, steady, and positive trajectory. Yes, the SEP suggests the Fed will soon begin to lower interest rates, but in this fantasy version of the economy, that will be followed by continued economic growth and stable employment.

That’s not what happens in real life, though. Note, for example, that over the past 30-plus years, that Fed rate cuts did not cap off a “soft landing,” but actually preceded the most vigorous period of job losses. As can be seen in the graph, cuts to the federal funds rate come several months before sizable increases in the unemployment rate. Sharp rate cuts began in 1990, for example, and the 1991 recession soon followed. Similarly, the Fed began to cut rates in late 2000, and then the unemployment rate soon accelerated upward. This again happened in 2007 when unemployment began to mount shortly after Fed rate cuts.

I’m not saying that the cuts to the federal funds rate caused rising unemployment, of course. I’m saying that the Fed knew there was no soft landing in the works, and knew that recessions were on the way. That’s why the Fed hit the panic button when it did, and cut rates in hopes of shortening the coming recession.

This reality makes it clear that there is absolutely no reason to believe Fed claims that it has everything under control, and that rate cuts will come only after the Fed has tightened just enough to rein in inflation without popping the many bubbles that fueled employment and consumer spending in the lead up to the recession.

In summary, this is how it has really worked: fearful that inflation is getting out of control, the Fed will raise the target interest rate and generally “tighten” monetary policy. Through it all, the Fed will insist there is no recession on the horizon and that a “soft landing” is in the works. Eventually, however, it becomes clear that the economy is substantially weakening and the Fed has been either lying about the economy or has been simply wrong. At that point the Fed then then does what it always does (in recent decades) when it fears a recession: it loosens monetary policy in hopes of blowing up a whole new series of bubbles to create a new boom period.

This is far cry from the sedate, measured, and perfectly controlled story of monetary policy that the Fed would have us believe.

The Fed Exists to Keep the Federal Government Funded with Easy Money

The second problem with Powell’s narrative is that the Fed is not motivated simply be concerns over the state of employment and the economy. While it would be nice to think the Fed is primarily concerned with the “everyman” and his job prospects, the reality is that the Fed is very much concerned with keeping borrowing costs low so that Mitch McConnell, Nancy Pelosi, et al, can keep buying votes and fueling the warfare-welfare state with enormous amounts of deficit spending.

Keeping borrowing costs low—by forcing down interest rates—is now more important than it has been in many decades. Over the past four years, the total federal debt has skyrocketed by 11 trillion dollars from $23 trillion to $34 trillion. In an environment of near-zero interest rates, this might be manageable. However, when this kind of debt is combined with rising interest rates, interest payments are rapidly rising and consuming ever larger portions of the federal budget. If the regime is not careful it could face a sovereign debt crisis.

When the Fed is able to force interest rates down without fear of runaway inflation, rising debt is not much of an urgent problem. As we can see in the graph, a rapidly rising federal debt did not lead to sizable growth in interest costs in the wake of the Great Depression. That, however, was during a period of very low interest rates. Since 2022, however, Interest costs on the debt have rocketed upward as the Fed has been forced to allow interest rates to rise.

In fact, interest costs have more than doubled since 2021. Yet, we’re not even seeing the full impact of mounting debt combined with rising interest rates. Interest costs over the past few years have been kept somewhat under control by the fact that federal debt does not mature all at once. In 2024, however, nearly 9 trillion dollars worth of federal debt will mature. That will need to be replaced with new debt which will need to be paid off at higher interest rates (i.e., at higher yields) than the maturing debt. Combined with the $2 trillion or so in new debt that will be added in 2024, the Federal government will need somebody to buy more than 10 trillion dollars worth of federal debt. That a whole lot of debt and the Fed will be expected to help the federal government somehow keep interest rates from rising further. This will require the Fed to enter the marketplace and buy up large amounts of debt in order to push down yields.

In other words, political realities will mean the Fed will have to embrace new rate cuts whether price inflation is at the two-percent goal or not. The Fed will say that price inflation has hit the “target” regardless of whether or not that is the reality. Since the Fed now defines its two-percent target in terms of averages and long-term trends, the Fed need only say that it has determined that the “trend” points toward falling price inflation.

Then, voilà, the Fed can get to doing what really matters to the federal government: laundering federal deficits by forcing down interest rates.

Yesterday, Jay Powell performed the usual song-and-dance that is the foundation of the central bank’s political legitimacy: claim it is skillfully managing the economy while claiming to be deeply concerned about the daily struggles of ordinary people who face the ravages of price inflation. The reality behind this routine is something very different.